New York to LA in 21 minutes

A look at the ambitious end of high speed trains.

I like the Hermeus slogan of making the world regional because it encapsulates a simple way to markedly increase people's quality of life. Everyone can relate to travelling regional distances, vs taking a long trip to a place far away. What if there were no places far away?

Exponential Progress

I recently saw a quote that went something like "If aerospace progress had advanced at the same rate as Moore's law in the semiconductor industry, planes would be flying 6 times the speed of light by now.". Of course, the semiconductor industry is an outlier. Progress is rarely exponential, and it's such a blessing to work in an industry during the midpoint of the largest S-curve the world has ever seen, so I have to keep reminding myself this sort of progress cannot be taken for granted.

In the mid-20th century, the aerospace industry was in the middle of it's S-curve, going from the Wright Brother's first flight in 1903 to landing on the Moon in 1969. My grandfather was a young father, and I can only imagine what must have been going through his head while watching a live broadcast from the Sea of Tranquility. Surely everyone would live like globetrotting billionares by the far-off year 2023?

And yet, no. We can travel marginally faster than he could in 1969, though admittidly at a much lower cost. Still, current commercial aviation leaves a lot to be desired. A seemingly obvious next step would be supersonic air travel, as the Concorde had in the previous century. As seen by my quote of Hermeus, I remain optimistic about the future of supersonic air transport. However, even assuming massive gains in efficiency and reliability of hybrid turbofan-ramjet engines, the time required to climb and descend in a supersonic (or hypersonic!) plane still places a lower bound on travel time.

Planes only make sense beyond ~800km

RAND in the 70s

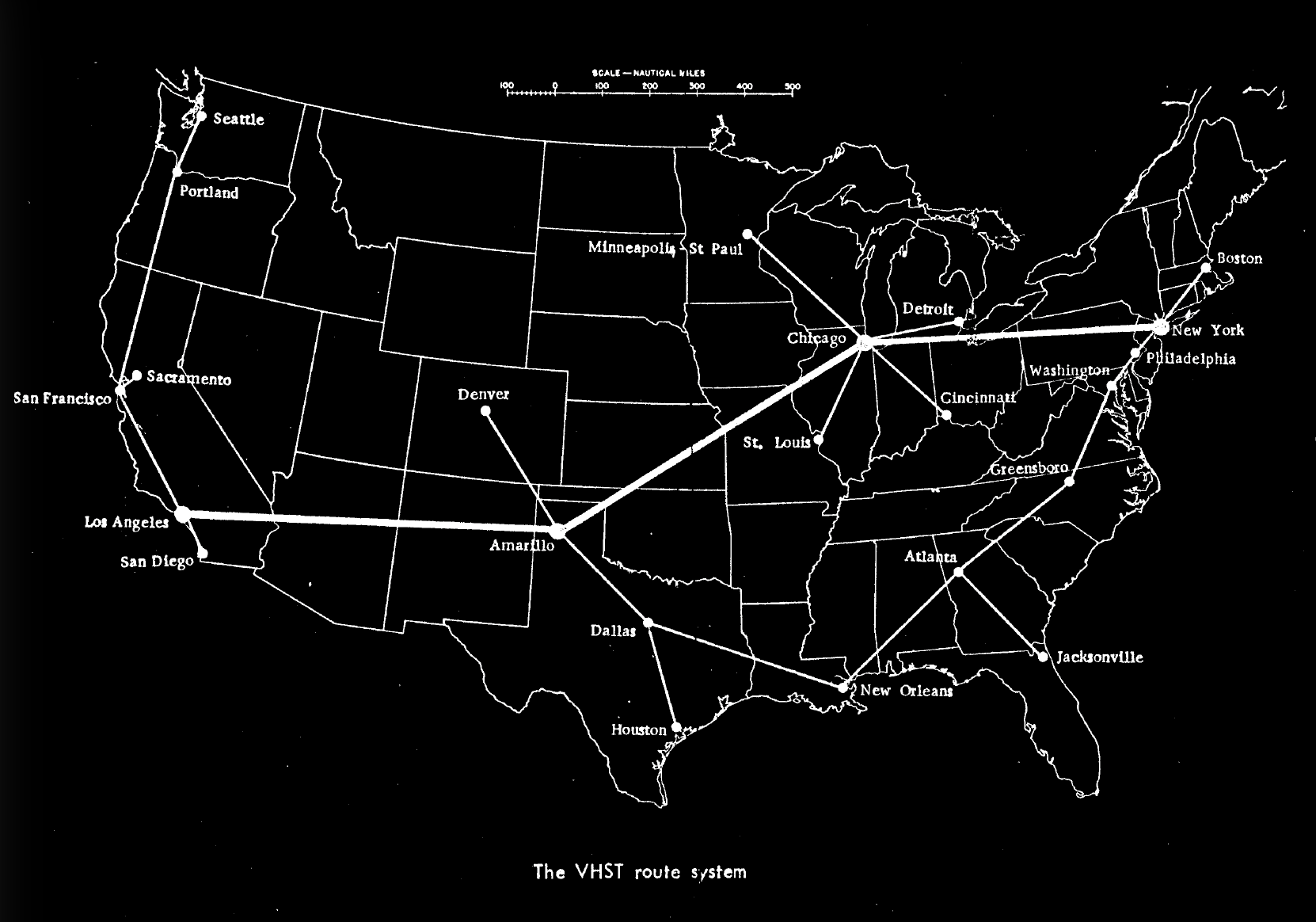

One proposal from the RAND corporation for an alternative to air-travel taken from the mid-70s is the Very High Speed Transport (VHST) system. It proposes mid-to-high vacuum tubes through which electromagetically levetating pods could travel at many multiples the speed of sound.

Isn't that just a hyperloop?

In recent years, the idea of a maglev train in an evacuated tube has gained media attention, partially due to a proposal by Elon Musk and several SpaceX engineers in 2012, called the Hyperloop. Since then, various startups have pursued the idea, nearly all resulting in failures. The promise of airplane-like speeds without the hassle of airports, takeoffs and landings is attractive. The renderings of sleek stations with comfortable-looking pods slipping in and out every few seconds looks like the way of the future. In hindsight, it's quite obvious why these companies failed, and perhaps some introspection beforhand could have saved venture capitalists heaps of money.

The primary challenges with a hyperloop are

- Maintaining large vacuum vessels is extremely difficult

- Very high speed trains require large-radius turns to minimise lateral G forces

- Aquiring land rights to large swaths of land in long straight lines is exceptionally expensive without emminent domain

- Going in a straight line through any elevation variation inevitably requires lots of tunnels

- Any privately funded transport system must operate high volume routes to recoupe investment

There are numerous other challenges, but those are the absolute showstoppers. The idea that this all could be solved in a few short years after you put out a few 3D renderings and raise a few hundred million dollars seems ridiculous in hindsight.

So are these challenges insurmountable? Are we doomed to max out at ~500 km/hr high speed trains?

Even More Insane

Ironically, the VHST proposal from the 1972 is far more aggressive in it's ambition than hyperloop, and yet sidesteps many of the hardest challenges.

The proposal outlines a system in which an entirely underground maglev train could operate in a partially evacuated tunnel, accelerating constantly until a midpoint, after which it decellerates. The proposed first line isn't a short Boston-Washington corridor, or a LA to Las Vegas sprint, but a line clean across the country from LA to New York. Over such a long distance, at 1 G of constant acceleration, let's do the math to work out how fast we'd go, and how long the trip would take.

LA to NY = 2445.55 miles 2445.55 x 1609.34 = 3,934,005 meters Halfway distance = 3,934,005 meters / 2 = 1,967,002 meters

The formula to calculate the final speed given the acceleration and distance is

v^2 = 2as v = sqrt(2 * a * s) = sqrt(2 * 9.8 m/s² * 1,967,002 m) = 6,209 meters per second

So, the peak speed (when the train reaches half way) would be approximately 6,209 meters per second, or 13,889 miles per hour. Assuming constant acceleration and decelleration, we can halve this to get the average speed:

av = v / 2 = 6,209 / 2 = 3,104 m/s = 6,943 miles per hourTo calculate the time it would take for the entire trip, we can use the formula:

t = d / av = 3,934,005 m / 3,104 m/s = 1,267 seconds = 21 minutes 7 seconds.Realistically this is the upper bound. Pasenger comfort demands a lower acceleration. An average airplane taking off accelerates at around 0.4 G (3.92 m/s²), so using that we get a top speed of:

v = sqrt(2 * 3.92 m/s² * 1,967,002 m) = 3,926 m/s = 8,782 miles per hour.And trip time:

t = 3,934,005 m / (3,926 m/s / 2) = 2,004 seconds = 33 minutes 24 seconds.This is a more realistic upper bound. No known technology can alter human perception of acceleration, so no matter how capable your transport system is, you will always be limited by the fleshy bodies inside. The Expanse does a fantastic job of illustrating what this means for space travel in the 24th century.

So now we know it's possible to go from LA to New York in the time it takes to enjoy a good dinner, how can we build this thing? And how on Earth is this more practical than a hyperloop travelling at 600 mph?

Underground

One of the biggest benifits of the VHST system is that it's entirely underground. This might seem like a huge source of cost (and it is), but it's the only factor that makes this feasible compared to a hyperloop-style system. What does going subterranian get us?

Vacuum

It's far easier to hold a partial vacuum in an underground tunnel, where the pressure vessel is supported by the earth around it, rather than a freestanding vessel exposed to the elements, under constant compression. This is vital as the vessel will need to hold partial vacuum (ideally over 99%) over thousands of kilometers.

Land accessibility

Most underground land held in the United States operates under seperate mineral rights. These are commonly bought up by oil and gas companies. Operating a VHST will demand purchasing parts of landowner's mineral rights, which typically are far less valuable than land rights, especially in areas with low oil and gas content.

Straight lines

If we want to travel over 8,000 mph, we basically can't turn. If we want to keep centrifugal forces under 1 G, our minimum turn radius will be 1,571 km at top speed. This entirely precludes going around mountains, rivers, lakes, or anything traditional high-speed rail would avoid. Fortunately we're underground already, so the only thing we need to worry about is maintaining sufficient depth as surface elevation changes, and resurfacing in time to reach stations.

(Side note, any hyperloop aiming at supersonic speeds is essentially infeasible for this reason anywhere but the flat midwest.)

So there's the first 4 issues checked off the list, how can we solve the demand problem?

Coast to Coast

This system will be one of the most expensive projects ever constructed, and recouping that investment within a lifetime requires operating exclusively high-volume routes. No Amtrack business model here! The top 3 highest volumn air routes in the US involve cities relatively close by (LA to Vegas, Honolulu to Kahului, Atlanta to Orlando). The fourth highest volume route is NY to LA, which conviniently happens to be one of the longest routes possible in the continental states. This route provides maximum benifit to riders (most saved time) while servicing the highest volume possible on a single route.

Additionally, we can have one or two intermediate substations part-way through which can also drive rider volume. For these, I think Chicago and Denver make the most sense, as they lie in a relatively straight line and each have large populations (2.69 M and 711 K respectively). Of course, stopping at these stations requires slowing down and surfacing, which decimates our coast-to-coast travel time, so it makes sense to operate both non-stop routes and shorter stopping routes.

Let's do the math on how much revenue these routes can generate. These will be based on 2018 numbers, which are the most recent I can find reliably, without the COVID aberation.

NY to LA: 3,635,655 NY to Chicago: 3,198,700 LA to Chicago: 2,927,492 LA to Denver: 2,519,514 NY to Denver: N/A (couldn't find)

Let's estimate an average ticket price of $100 for all routes (in reality it's a bit higher, but we want to compete).

(3,635,655 + 3,198,700 + 2,927,492 + 2,519,514) * 100 = $1,228,136,100 / year

Ok, so if we can service every passenger along these routes (we'll discuss servicable volume below), we'll get around $1.2B in annual revenue. Does this cover the cost of construction + operation?

Costs

This is the point at which this post will devolve into pure speculation. I realistically can't know how much it will cost to build this thing once regulatory roadblocks arise, and with mass production of components. What I can do is try to set an upper bound on cost by looking at similar (albiet smaller) projects cost today and factoring in some amount of advancement in tunneling efficiency.

As stated before, one of the key advantages of this system is that it's entirely underground and so foregoes any costs associated with acquiring surface land and building surface tubes. What that means is that the lion's share of the cost is in tunneling. So how expensive is tunneling? Let's ignore the partial-vacuum aspect of our tunnel for now, and just look at standard rail tunnel rates. International Railway Journal puts the cost in China at around $10-15M per km. We'll use that as a starting point, since they've built large amounts of rail tunnel most recently, and so those costs will reflect more recent construction techniques.

3,934 km x $10M = $39.3B $39.3B / $1.2B = 32.75 years

So we have the time it would take to pay off the system, if the only cost was the tunnel alone.